Avant-garde

|

Russian avant-garde art

The great surge of works on Russia’s past and present, interpreted in many unexpected, original and different ways, resulted in a multi-coloured kaleidoscope of the various styles in the art of the turn of the century. Such diversity did not, however, imply decline or confusion. On the contrary, it testified to the free, full-blooded and unfettered nature of Russian culture at the start of the new century. It is not surprising that this period witnessed the maturing and formulation of aesthetic ideas, ones principally new for the art of the twentieth century. The Rayonism of Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964), the abstract art of Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) and the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935) and associates all owe their appearance to the abundance of non-abstract art. The Russian Museum owns a fine collection of Russian avant-garde art, representing practically every trend, name and movement in this branched process that confirmed the new aesthetical ideas and means of artistic expression. The start of the twentieth century saw the widespread influence of modern Western art on Russia. Russian artists travelled widely across Europe, while Moscow and St Petersburg were home to the private galleries of Ivan Morozov and Stepan Schukin. These contained paintings by Paul Cйzanne, Henri Matisse and other twentieth century innovators at a time when they had still to achieve world fame. All of this rendered an undoubted influence on the path and nature of Russian art. Followers of Cezanne soon appeared in Russia. They formed a group bearing the revolutionary name Jack of Diamonds and reinterpreted “Cezannism” in a highly original and typically Russian manner. The still-lifes, portraits and landscapes of Ilya Mashkov (1881–1944), Pyotr Konchalovsky (1876–1956), Alexander Kuprin (1880–1960) and Aristarkh Lentulov (1882–1943) employ the painterly, plastic and thematic tackiness of Russian folklore art (shop signs, toys, lubok prints) alongside devices typical of Cezanne. Now they are held in museum collections, including that of the Russian Museum, on an equal footing with their pictorial canvases. Up until the end of the nineteenth century, distaffs, trays, wooden and clay toys, embroidered towels and clothes were merely part of the everyday life of peasant households. The Jack of Diamonds artists resurrected them as works of art in their own right. Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) were possibly the first to depart from the narrative nature of the old art and accentuate the simplification of form. Attention to the folk art of various countries, among them Russia and the Ukraine, enriched the palette and plastics of these artists and left a bright trace in Russian art. Nathan Altman (1889–1970) and Marc Chagall (1887–1985) lived long creative lives, progressing from an initial interest in French Cubism. Even their early works carry the spark of their creative independence. Their works of the mid-1910s rank amongst the best examples of Russian avant-garde — Altman’s Portrait of Anna Akhmatova (1914) and Chagall’s Promenade (1917). Lyubov Popova’s (1889-1924) oeuvre from 1913 to 1916 is a classical example of Russian Cubo-Futurism. The child of the marriage of French Cubism and Italian Futurism on Russian soil, Cubo-Futurism nevertheless possessed its own unique national specifics. An artist who sadly died young, Olga Rozanova was one of the most talented members of the Russian avant-garde. After an initial period of interest in Expressionism, Wassily Kandinsky officially proclaimed his adherence to abstract art in 1911. The Russian Museum possesses more than twenty works by Kandinsky, which trace his development from Expressionism to abstract art. Kandinsky orientated himself on sensations born of the subconscious. Form in his works is defined by colour, rhythm and spots. Here Kandinsky was close to the icon-painters and masters of folk art, from whom he derived much inspiration. Kazimir Malevich came to his personal revelation of Suprematism via Impressionism, Cubism and Cubo-Futurism. His heritage (more than a hundred pictures and some twenty drawings) is better represented in the Russian Museum than anywhere else in the world. The pictures of his Impressionist and Symbolist periods, the Cubo-Futuristic Portrait of Ivan Kliun (1911) and Aviator (1914), his Suprematic compositions of 1915 and 1916 and his series of peasant men and women of 1928–32, uniting figurative art with Suprematism, are the pride of the Russian Museum. Ivan Kliun (1870-1943) was one of the first followers of Kazimir Malevich and perhaps his most stoic confederate. The formulatory basis of Suprematism united in Jean Pougny’s (1892-1956) oeuvre with reality, a reminder of which are various objects, words, fragments of words and details from everyday life. Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956) clearly received the impulse that led him along this path from Kazimir Malevich. Unlike Malevich, however, Rodchenko was a true materialist and in essence closer to Vladimir Tatlin (1885—1953) and his relationship with art as a handicraft and the process of creation as one of invention. Although works by Vladimir Tatlin are not often encountered in art collections, the artist remains one of the unchallenged pioneers of the Russian avant-garde. Just as complete and unique is the collection of works by Pavel Filonov (1883–1941). Almost two hundred paintings and more than two hundred of his drawings and watercolours were presented to the Russian Museum by his sister, Yevdokia Glebova. Filonov developed his own personal technique, to which he gave the name “analytical”. It can be traced from his early compositions (Shrovetide 1913(4?) and The German War 1915), which reveal Filonov’s bright individuality alongside noticeable links with folklore, right through to his mature works. Filonov arranged his pictures like plants growing in nature. His compositions were often similar to mosaics or pictures in a kaleidoscope. Yet beyond the form — original and aesthetically attractive — lay profound, philosophical meditations on man and the surrounding world. |

Larionov M. Venus. 1912 Larionov M. Venus. 1912 |

Malevich K. Suprematism. 1915–16 Malevich K. Suprematism. 1915–16

|

|

Mashkov I. Lady with Pheasants. 1911 Mashkov I. Lady with Pheasants. 1911

|

|

Goncharova N. Peasants. From the Picking Grapes nine-part polyptych. 1911 Goncharova N. Peasants. From the Picking Grapes nine-part polyptych. 1911

|

|

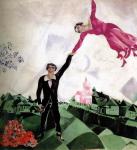

Chagall M. Promenade. 1917 Chagall M. Promenade. 1917

|

|

Tatlin V. Sailor. 1911 Tatlin V. Sailor. 1911

|

|

Filonov P. The German War. 1915 Filonov P. The German War. 1915

|